Covid-19 and the Technicolour Dreamcoat

Covid-19 and the Technicolour Dreamcoat

By David McIlroy 09 Jul 2020

If your knowledge of Joseph and the famine comes solely from Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, then its relevance to the current coronavirus crisis may have escaped you.

Joseph’s economics

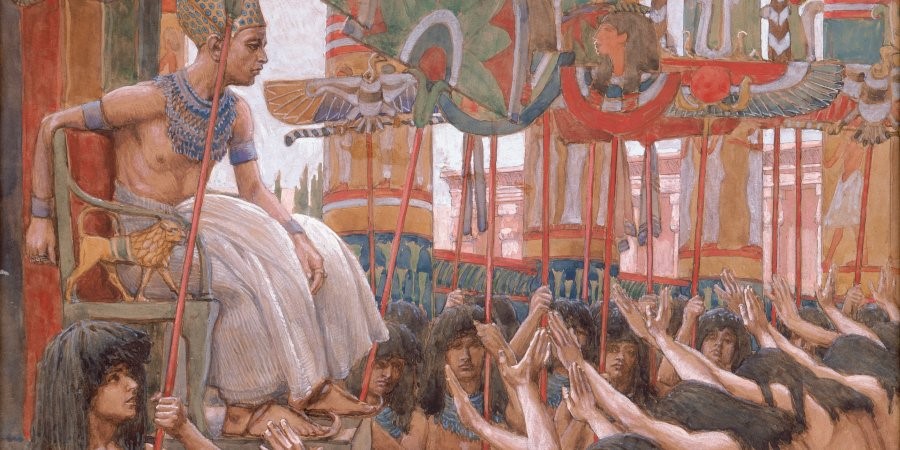

Joseph's story, re-told in economic terms, goes something like this: Joseph, the arrogant favoured son of a successful farmer, is sold by his brothers into slavery in Egypt. After learning micro-economics running the household of a wealthy official, Joseph is falsely accused of rape and ends up in prison. There, through his dreams, Joseph is given miraculous insight into the economic cycle: the 7 years of plenty are going to be followed by 7 years of famine (Genesis 41:25-27), and unless resources are stockpiled in the good times, disaster will follow and many lives will be lost. Joseph interprets the dream to Pharaoh, who promotes Joseph to a role in the finance ministry. Joseph places into a reserve account one-fifth of all of Egypt’s produce in the good times, meaning that Egypt has enough resources to provide for its people and save many lives through the economic recession (Gen. 41:34, 47-49).

Thus told, the story of Joseph seems an indictment of the choices made during the ‘good times’ by politicians, companies and individuals to rely on debt to fund expenditure on consumption, leaving the economy in peril during the present crisis.

However, there’s a more significant warning hidden in the story of Joseph’s state aid project—one that Andrew Lloyd-Webber didn’t make a song and dance about.

The writer of the Book of Genesis is, in fact, more than a little ambivalent about Joseph’s measures. Joseph’s relief plan was not a ‘free lunch’. Instead of an interest-free loan or a grant, he offered the stockpiled grain for cash (Gen. 41:56). His policy succeeded initially, but as the famine continued the Egyptian people ran out of things to sell. Once Joseph had collected all the money, he agreed to sell grain to the people in exchange for their livestock (Gen. 47:16). This enabled them to survive another year but at the cost of all their domestic animals (v.17). But as the famine continued, the people became desperate and implored Joseph:

‘Buy us and our land in exchange for food, and we with our land will be in bondage to Pharaoh. Give us seed so that we may live and not die.’ (47:19)

As business owners and families became more and more impoverished, they had nothing left to offer but themselves.

Joseph’s response to the famine may have kept the Egyptians alive, but it ‘reduced the people to servitude, from one end of Egypt to the other’ (47:21). At this point in the story, Joseph adopted a more lenient policy. He distributed seed for the people to sow, to be paid for by one-fifth of the crop produced going to Pharaoh (47:23-24).

The story of Joseph’s management of Egypt’s resources is also the story of how the Hebrews came to be enslaved in Egypt. It is a parable telling how even a relatively successful programme of government relief in a time of crisis can lead to profound changes in the economy which are deeply unfair and destabilising once the immediate crisis has passed.

Alpine ranges of debt

The current coronavirus crisis, and the UK government’s response to it, is creating not just a mountain of debt—but a whole Alpine range. Dealing with that debt could take one of three forms:

1. The UK government deals with its own debt by increasing taxes and further nationalising the economy. The government would no longer work for its citizens, instead citizens will work for the government. Meanwhile, private debt is left to the market to adjust through processes of existing insolvency laws. This will lead to a wealth transfer from those whose livelihoods have been destroyed (restaurant owners, some retailers, small hoteliers) to those with the means to buy up assets on the cheap.

2. The impact of the debt is reduced through the dubious magic of inflation. With the Bank of England base rate at 0.25%, we have forgotten that double digit inflation was the tool by which the UK and other governments in the 1970s managed to afford to repay the debt they accumulated during the oil crisis and other economic shocks. Some economic commentators are already warning that once the crisis is over, we are facing a decade of stag-flation (a toxic combination of stagnation and inflation), in which prices rise rapidly but with no recovery in profitable economic activity.[1] Stag-flation brings its own winners and losers; winners use their money to purchase rapidly appreciating assets (locking in inflation-proof gains), while the losers include those subjected to long term unemployment, or pensioners whose incomes are fixed.

3. Adopt the radical economic policy built into the constitution of the society the escaped Hebrew slaves established in Israel: Jubilee. The uneven accumulation of capital can lead to a situation in which the rich get richer while even the little the poor have is taken away from them (think Monopoly). Recognising this, the Year of Jubilee was a period of cancelling debts and redistributing property so that every family had a chance, once in every two or three generations, to regain a meaningful stake in the country’s prosperity. In our own time, the burden of the quarantining measures has fallen disproportionately on some and not others. Some industries have been devastated; for others it’s business as usual or even new opportunities for profit.

The warning

The real story of Joseph tells us that desperate people are prepared to accept whatever terms they can get in order to feed their families. It warns that when we emerge from this crisis, the poor might owe everything to the government, or to those oligarchs who snapped up bargains from those with no choice but to sell all they own.

There was an explosion in books warning about the social and economic dangers of rising inequality in the decade before the coronavirus crisis.[2] We risk emerging from the crisis into a world more unequal than ever.

The Year of Jubilee challenges us to think the unthinkable: a hard reset of the UK economy with forgiveness of the debts accumulated during the crisis.

[1] Victor Li, ‘What will come in the aftermath of coronavirus for economy? I’d worry about stagflation’, 19 March 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/19/what-comes-after-coronavirus-for-economy-worry-about-stagflation.html; Bryan Caplan, ‘I fear stagflation and price controls are coming’, 18 March 2020, https://www.econlib.org/i-fear-stagflation-and-general-price-controls-ar...

[2] Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2014) is the classic text, but Piketty has also published Capital and Ideology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020). Other important works include Joseph E. Stiglitz 2013; The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers our Future (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2013); The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016); Chuck Collins Born on Third Base (West River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2016); Branko Milanovic Milanovic, Branko. 2011. The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality. New York: Basic Books, 2011); Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016); Ganesh Sitaraman The Crisis of the Middle-Class Constitution: Why Economic Inequality Threatens Our Republic (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017); Heather Boushey, Bradford DeLong, and M. Steinbaum, After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017).